STATE STREET

Kenny lost control of his flatbed pickup on State Street on the evening of January 6th, 1982. Just west of Brownhill road, the truck slid across the center line and careened into the ditch; the truck jumped a creek and slammed head on into the opposite bank. He was dead at 32.

Brett had borrowed Tisha’s Datsun 1200 in May of 1986. He and Mark and Pam picked up Bart to go joyriding on country roads. Brett turned from State Street to Burma and drove north to Armstrong Road. Not used to country roads, Brett lost control about one mile as the crow flies from Bart’s house. The car spun backwards on the road and flipped on to its side in the ditch with a bone-rattling thud. Brett was ashen and cussing. Bart was bleeding a bit. For a second Mark thought Pam was dead.

Bart was riding shotgun with Lance when the 280 ZX they were in drove off the west end of State Street at 110 miles per hour, skidded, and wrapped around a tree on December 20, 1986. Bart was dead at 17. His parents lived on the same road, nine miles to the east.

Carmen Asebado, just nine, was killed less than a mile from State Street on July 18, 2016. She was in Chevy Trailblazer with her sister and four cousins, heading west on K-140. A young woman, Joslyn Geiber, heading south on Burma Road, failed to yield and clipped the Trailblazer, which flipped, landed on its top and tossed Carmen out of the car.

I came upon this last crash just a few minutes after it happened.

Arranged on a map these wrecks would form four dots that could be a triangle with a straight line out of its top that points West to the end of State Street. Conversely, the accident sited could be plotted to take the shape of an arrow facing to the East. I can only pretend to press some symbolism into these events. What I do know: these accidents on and near State Street left me with tons of twisted steel, bittersweet memories, corpses, and an abiding sense of personal failure.

* * *

When my brother and I came home from school that Thursday, the house seemed overly quiet. The folks didn’t work Thursday afternoons, and the house was attached to the office where my father pushed vertebrae back into the place. It was also the house where my step-mother Ginny had grown up, and she sat at the same typewriter where her mother had sat. At the kitchen table, Dad told us Kenny was dead. A car accident on State Street. But he was at the house just the night before, I said. There were police involved, Dad said, but no one was in trouble. Except Kenny, I thought. And his wife Denise.

Raucous and full-bearded, Kenny was a gregarious fellow with a love of farming and a hankering for homegrown grass. He had moved from the city to try his hand at growing various crops. A local farmer didn’t take kindly to this interloper and shot Kenny’s German Shepard, Mabel. Kenny responded by sabotaging the neighbor’s milo field.

Kenny encouraged my brother and me to explore around his acreage that backed up to Mulberry Creek, and we played guns around the barn and outbuildings. In the evenings, we would sit around the dining room table, Sports Illustrateds cluttered about and try to draw our college basketball heroes while Kenny and Denise and our folks partied in the front room. But Kenny also made us work. In the fall before his passing, we had to help cut and stack wood. Kenny had rigged up a hydraulic log splitter on a trailer and had hauled it to the trees near the creek. He let me push the stick of the cutter forward, and I could feel the vibrating force of the machine as the blade cleaved the oaks. Near sundown we loaded our trunk with wood and drove back home via State Street.

* * *

My grandpa drove the Sunday Buick out State Street to Hedville Road on the way home from church. It was on State Street, heading slightly downhill into town, that I was able to push my 1975 Mustang II past 100 miles per hour in 1986. My friend James lived on State Street just inside town, literally on the wrong side of the tracks. Charlie Walker owned a huge chunk of land along State Street that he would eventually turn into an exotic zoo. When I was in kindergarten, I had to walk down to Hedville Road to catch the school bus. The bus turned left on State Street and eventually picked up Bart, and hauled us to Happy Corner Elementary. On his sixth birthday, Bart had a party and invited the kids from school. We got to get off the bus at Bart’s house. And it is in a township cemetery nary a mile north of State Street that Bart is buried.

I turn up Muir Road from State Street to visit Bart’s grave on July 18, 2016. An oval color picture adorns the stone, his whisp of a mustache above his forever grin. He’s clad in a pink shirt. I had been to this spot maybe a dozen over the last 30 years, and my routine has always been the same. I put my hand on the stone, kneel down, and breathe in the country air that I so miss. Bart was my first real friend. He swayed his head from side to side when he ran. His folks were strict, but he still found a way to raise all kinds of hell. We went to the lake with his brother, sat on the sand, and drank beers and acted older than we were. His fake ID was the reason we got beer on my sixteenth birthday. Bart was my first friend to die.

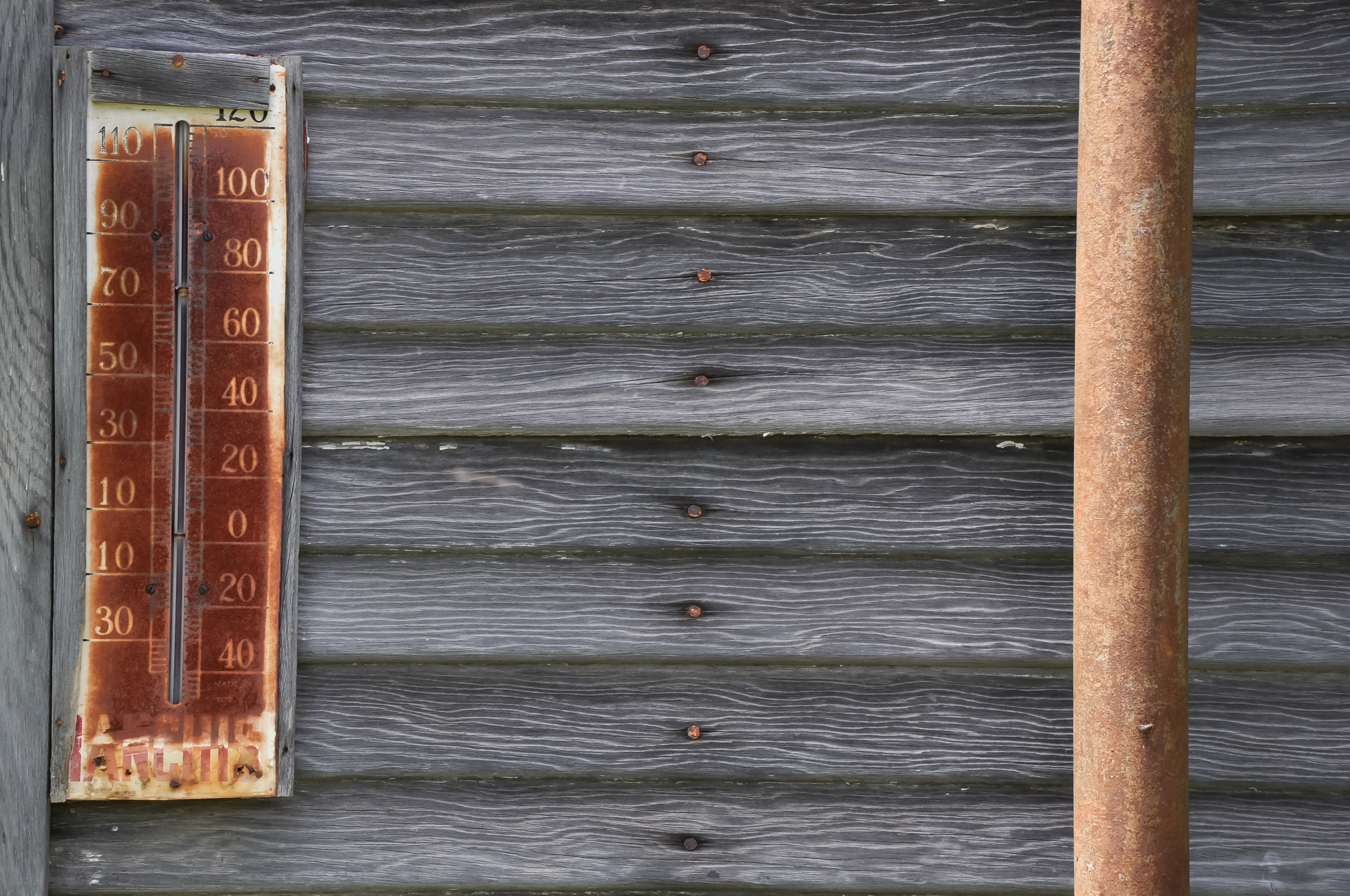

Earlier this day I had been photographing an abandoned homestead in north central Kansas. I had permission and nothing but time. I worked my way slowly through the crumbling house, rotting vehicles, and assorted outbuildings. After three hours at the location, I was done. I had only a few days earlier discovered, after years of shooting, what exactly all this photography of decay was - the weathered beauty of the rips and mends of memory, the patina of my soul. Today might have been my best day of shooting.

I headed south and went through Culver. For years our family had lived on a quarter section, land my grandfather had bought and farmed since we were little kids. I spent the summers of my youth there and worked harvest, fed cattle, dug thistles, hunted birds, rode motorcycles and caught fish. When my grandmother passed, my Uncle sold the land (except the 10 acres around the house, which my folks owned) without telling anyone. The house was sold but a year later. I got out of the car down near the Morton building wondering if I would hop the gate and shoot a few furtive photos. Instead I simply stood there, the melancholy bubbling as I recalled feeding the cows and pigs, as well as my paralyzing fear of grandpa’s bees. When I had first started shooting pictures as an adult, it was at this very place where I no longer had permission to be.

* * *

When I leave Bart’s grave and head back to State Street, I think about stopping to visit his parents. I had seen them a few times over the years, but always felt a sense of unease at sharing anything remotely happy. Within a couple of minutes I reckon they simply don’t need to be reminded. I would be imposing. A film of dirt has baked onto my arms and face, and dried sweat leaves salt marks on my shirt and hat. It’s getting on toward dinner time, anyway, so I can take Burma Road — the last right before Bart’s house — and head back to Lindsborg. While creating these reasons not to stop, I miss my turn, slow near the family’s home, and continue another mile and half to double back and catch Old 40 back to Burma - a five minute detour.

I come upon the last crash minutes after it happens. A man stands in the roadway. I roll down my window. He asks frantically, “Are you a first responder?”

“No.”

“This is bad,” he says. When he leans into the car I can smell the cheap whiskey. “Are you a first responder?”

“No.”

“I am going to go now. This is bad.”

I pull into the gravel on the northeast side of Burma Road. A Dodge Nitro sits on the highway with its front end accordioned. In the ditch, another vehicle lies upside down and smoking. I think about grabbing the camera. I don’t. Instead, I think how I could help. I have beef jerky. I have water. There are a passel of kids standing feet from me. One of them screams, “Please don’t die. Please don’t die. I don’t want my sister to die. I don’t want my sister to die.”

I have water. I have beef jerky. I should get out and help.

Instead I sit in my car, unable to do anything except wonder why the ambulance isn’t here yet. When the sheriff shows up, he walks to the accident site. I am of no help. I drive off and phone the newspaper, like a good former reporter, to tell them there is an accident with a probable fatality at Burma Road and Old 40. They are already on it.

The next morning the Salina Journal has a small item about the crash. I learn that the dead sister’s name was Carmen Asebado, and she was nine-years-old. I did nothing to help her siblings, cousins, or aunt and uncle. Later that afternoon, I go back to the site and photograph what’s left of the wreckage.